Here’s how global warming will change your town’s weather by 2080

A clever study finds modern analogs for what our cities will feel like in 2080.

If you hate the heat, you may have morbidly joked that you’ll have to move north to escape the impending wave of climate change. That’s true—but you may have to go further than you think.

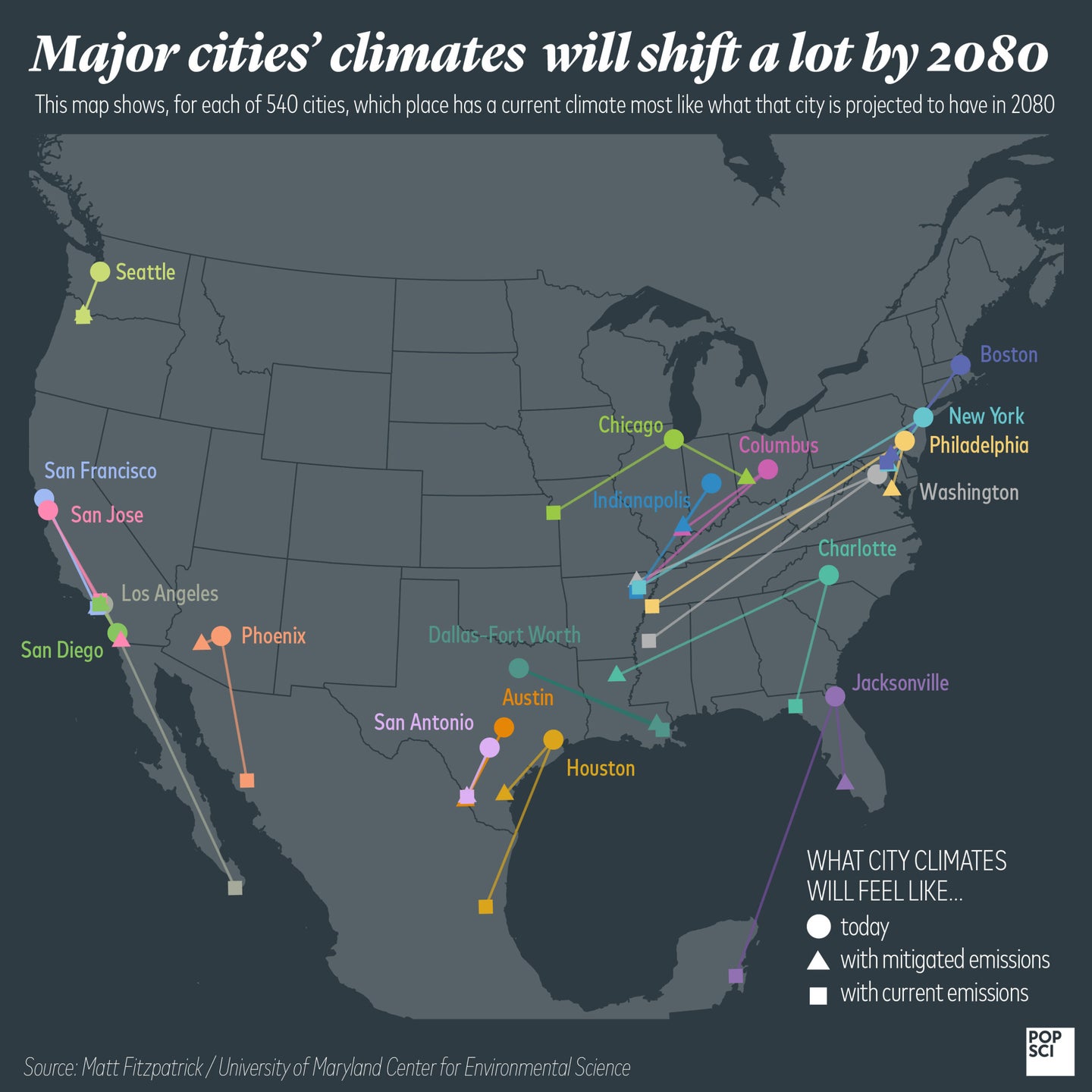

In 2080, New York City will have a climate much like Lake Shore, Maryland. Seattle will look more like Portland, D.C. will be more akin to Paragould, Arkansas, and Austin’s closest analog isn’t even in the U.S. (it’ll be more like Nuevo Laredo, Mexico). These estimates are all courtesy of a new study in Nature Communications that finds modern analogs for what the climates of 540 North American cities will look like in about 60 years. On average, the closest analog for the 2080 climate for each city was about 528 miles away, and mostly to the south.

The fact that Boston will feel like Aberdeen, Maryland in 60 short years should drive the impact of global warming home for you. And that’s what Matt Fitzpatrick, an ecologist at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and one of the two authors on the study, is hoping for. “I kept constantly hearing in the media about a 3°C increase in mean global temperature, or about the Paris Climate According keeping the change to 1.5°C. That just never resonated with me,” he says. In his normal scientific research, he uses modeling to figure out how climate change might impact where other species can live, so he wondered whether he could use similar techniques to note the shift’s impact on humans.

Most of the East Coast will start to look a lot more like the South, and many parts of the South will start to look like Mexico. You can see an overall trend with all 540 cities plotted, but let’s zoom in on the top 20 most populous cities in America. (Bonus: you can look at an interactive version of this map made by the researchers here, where you can search for your home town).

In a lot of cases, you can see just how big a difference the degree of emissions makes. Even if we manage to reign them in significantly, every city on here will have significant changes in their climate. And if we keep going at our current rate, well, we’re even worse off.

Some of these points go so far south they’re nearly off the map. And in fact, it’s worth noting that for a number of these cities, there weren’t even accurate analogs to point to.

In their study, Fitzpatrick and his co-author focused on the western hemisphere above the equator, but for many of the cities, there simply wasn’t a good comparison. They calculated mathematically how close each urban area was to its closest analog with a value called sigma—a sigma less than two indicates a pretty good match. Above two means it’s not great, but Fitzpatrick explains that they considered 12 different climate variables—sp that high sigma could simply mean the precipitation amounts weren’t a good match, for example.

A sigma over four, though, meant that there was truly no accurate analog above the equator. “Had we looked globally we may have found a closer analog in India or Africa,” Fitzpatrick says. “But once you do that, people aren’t gonna know what some town in India feels like.” If the point is to make climate change feel real, they had to stick within a relatively familiar area. But there are quite a lot of cities that won’t look like anything we know in the U.S. “What was surprising was how many of the cities, especially under [the higher emissions scenario], were off the charts, if you will, in terms of their non-analog-ness.”

With that many cities changing so drastically, Fitzpatrick notes that his grandchildren are unlikely to recognize the climate he lives in today. And hopefully his work can help people realize the impact of that change. “If you want to broadly lump people, there are those for whom there’s no amount of evidence or information that will change how they feel. And there are people on the other side that have seen enough, they understand the risks. But there’s also a lot of people in the middle that have heard a lot in the media, but it hasn’t really resonated with them,” Fitzpatrick explains. “My hope is that this helps those people have a ‘wow’ moment.”