Lab-made ‘super melanin’ speeds up healing and boosts sun protection

The synthetic pigment could be used in everything from military uniforms to cancer treatments.

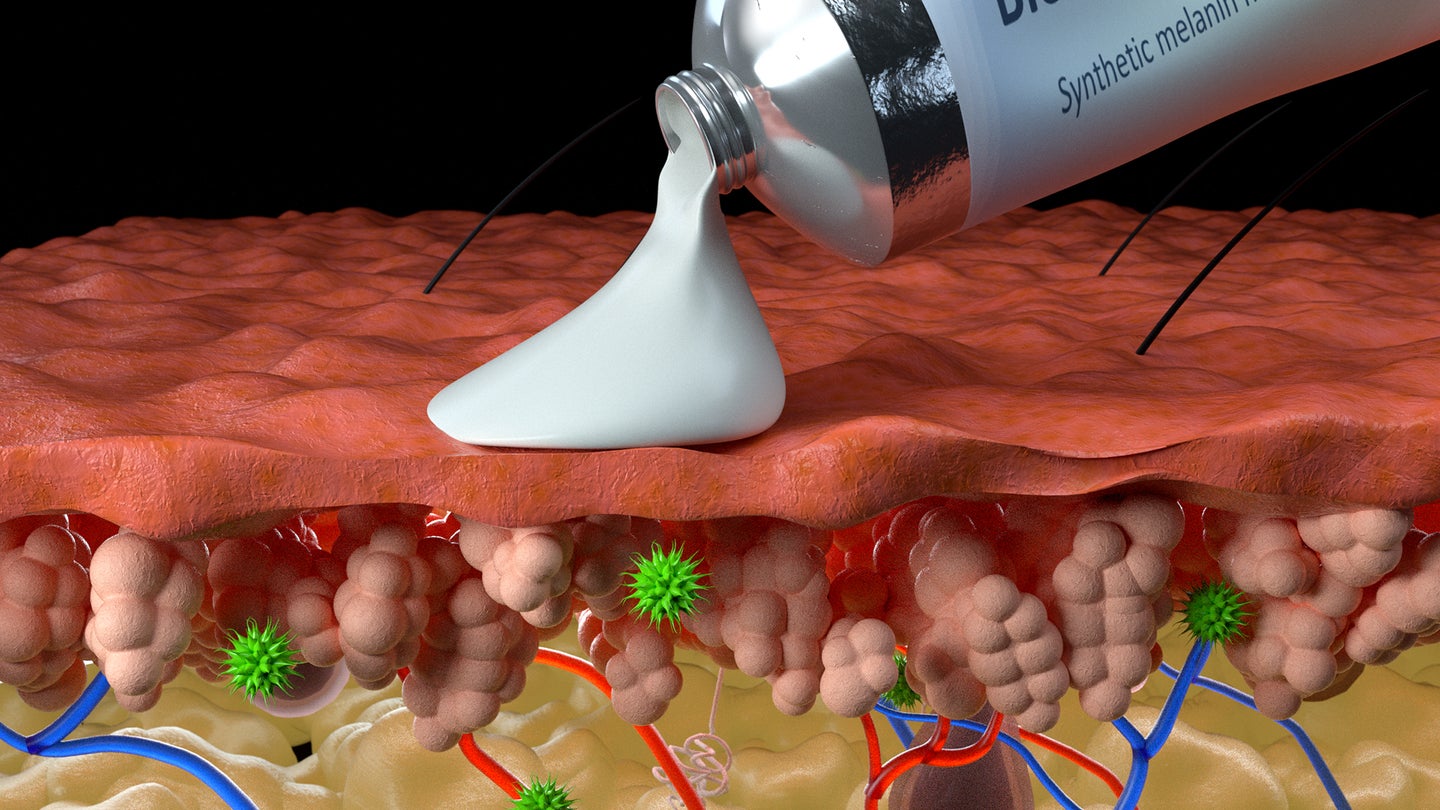

A team of scientists at Northwestern University have developed synthetic melanin that can accelerate healing in human skin. It is applied in a cream and can protect the skin from the sun and heal chemical burns, according to the team. The findings are described in a study published November 2 in the journal Nature npj Regenerative Medicine.

What is melanin?

Melanin is a pigment that is naturally produced in humans and animals. It provides pigmentation to the hair, eyes, and skin. It protects skin cells from sun damage by increasing pigmentation in response to the sun–a process commonly called tanning.

“People don’t think of their everyday life as an injury to their skin,” study co-author and dermatologist Kurt Lu said in a statement. “If you walk barefaced every day in the sun, you suffer a low-grade, constant bombardment of ultraviolet light. This is worsened during peak mid-day hours and the summer season. We know sun-exposed skin ages versus skin protected by clothing, which doesn’t show age nearly as much.”

[Related: A new artificial skin could be more sensitive than the real thing.]

Aging in the skin is also due to simply getting older and external factors like environmental pollution. Sun damage, chronological aging, and environmental pollutants can create unstable oxygen molecules called free radicals. These molecules can then cause inflammation and break down the collagen in the skin. It is one of the reasons that older skin looks very different than younger skin.

‘An efficient sponge’

In the study, the team used a synthetic melanin that was engineered with nanoparticles. They modified the melanin structure so that it has a higher free radical-scavenging capacity.

Researchers used a chemical to create a blistering reaction to a sample of human skin tissue in a dish. The blistering looked like a separation of the upper layers of the skin from each other and was similar to an inflamed reaction to poison ivy.

They waited a few hours, then applied their topical melanin cream to the injured skin. The cream facilitated an immune response within the first few days, by initially helping the skin’s own free radical-scavenging enzymes recover. A cascade of responses followed where healing sped up, including the preservation of the healthy layers of skin underneath the top layers. The synthetic melanin cream soaked up the free radicals and quieted the immune system. By comparison, blistering persisted in the control samples that did not have the melanin cream treatment.

“The synthetic melanin is capable of scavenging more radicals per gram compared to human melanin,” study co-author and chemist/biomedical engineer Nathan Gianneschi said in a statement. “It’s like super melanin. It’s biocompatible, degradable,nontoxic and clear when rubbed onto the skin. In our studies, it acts as an efficient sponge, removing damaging factors and protecting the skin.”

According to the team, the super melanin sits on the surface of the skin once it is applied and isn’t absorbed into the layers below. It sets the skin on a cycle of healing and repair that is directed by the body’s immune system.

[Related: The lowest-effort skincare routine that will still make your skin glow.]

Protection from nerve gas

Gianneschi and Lu are studying using melanin as a protective dye in clothing. The thought is the pigment could act as an absorbent for toxins, particularly nerve gas.

“Although it [melanin] can act this way naturally, we have engineered it to optimize absorption of these toxic molecules with our synthetic version,” Gianneschi said in a statement

They are also pursuing more clinical trials for testing their synthetic melanin cream. In a first step, they recently completed a trial showing that the synthetic melanins do not irritate human skin. Since it protects tissue from high energy radiation, it could also be an effective treatment for burns cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy often experience.

This research was funded by the United States Department of Defense and the National Institutes of Health.