There’s a lot we don’t know about the International Space Station’s ocean grave

The 450-ton station will follow a long line of retired spacecraft that have been laid to rest in the marine 'space cemetery.'

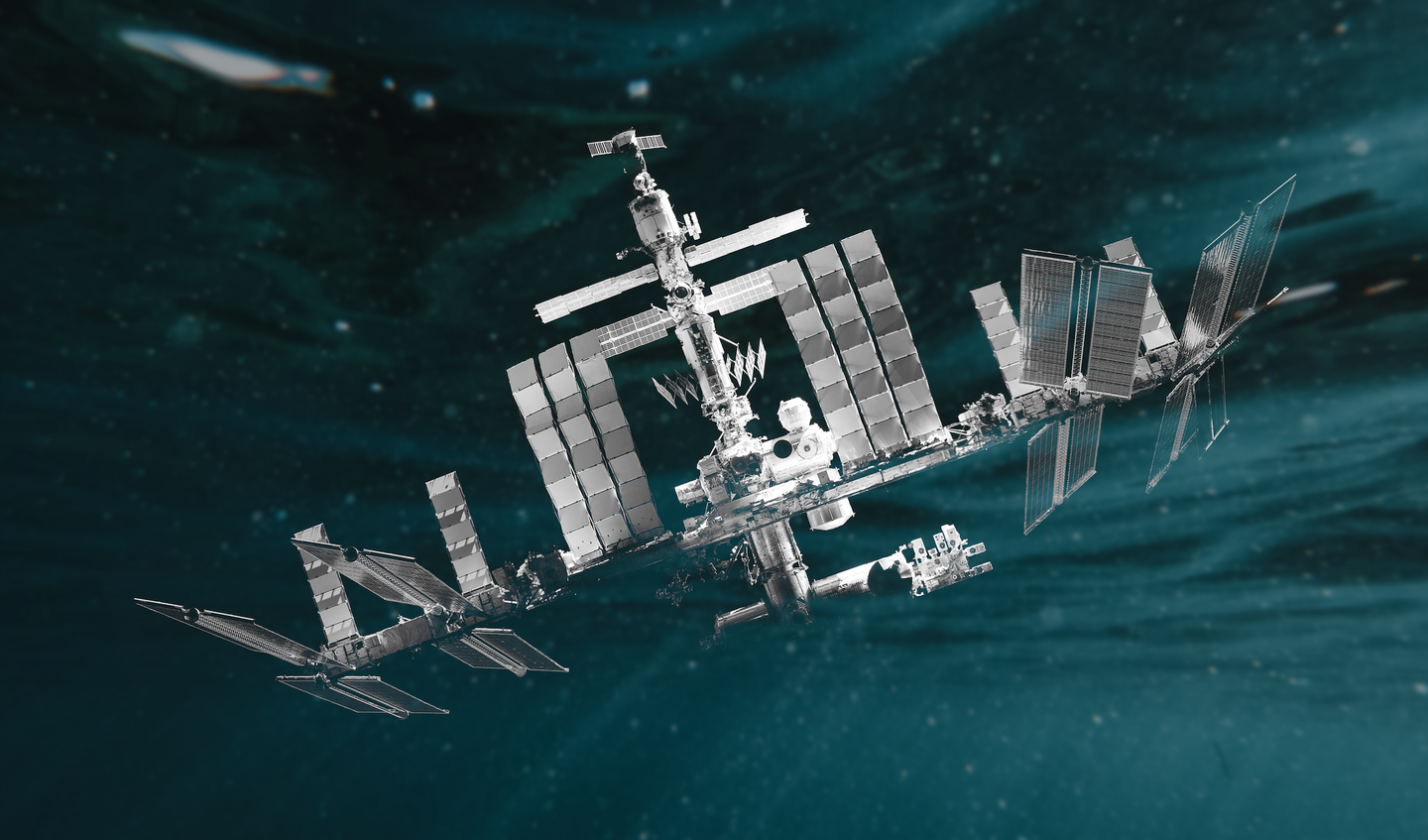

After more than two decades of scientific service, the International Space Station (ISS) is expected to bid a final farewell. The research hub has allowed us to expand our understanding of Earth, the solar system, and beyond. More than two hundred astronauts have visited the station, while researchers have conducted thousands of experiments and studies—from tracing the origin of stars to understanding the impacts of space on the human body. This space laboratory has touched and transformed nearly every major scientific discipline.

Earlier this year, NASA announced plans for the station’s eventual retirement in 2031, but it’s unlikely that the 450-ton lab will meet a quick demise. Once operations end, most dead satellites drift out of orbit and eventually burn up in Earth’s atmosphere.

However, most of the ISS will sink into Point Nemo, a remote area of the Pacific Ocean so far from land that many scientists refer to it as a “space cemetery,” after the number of spacecraft laid to rest in the watery grave.

The isolated stretch of ocean is an ideal location for a spacecraft to crash without causing any potential harm to humans or destruction to cities, as NASA describes in the ISS’s transition plan. The name “nemo” is Latin for “no one” and just as the moniker implies, it’s uninhabited by humans. In fact, it’s the furthest point from any landmass on Earth.

There’s hardly any life in the nutrient-poor waters—the lack of biological diversity is one of the reasons Point Nemo is used as a galactic dumping ground. At one time, Point Nemo offered a perfect blank canvas to study a deep underwater location completely untouched by the human environment, says Leila Hamdan, associate director of the school of ocean science and engineering at the University of Southern Mississippi. Hamdan studies deep sea biogeography—particularly, how shipwrecks change the biodiversity of the ocean floor.

But large technology exposed to the elements of space presents a whole different set of unknown variables. With the clock ticking on the ISS’s impending watery doom, some are questioning how space exploration ultimately impacts marine life.

“Before we even had the technology to go [to Point Nemo], and put deep submersibles in the ocean and collect samples from that location, we’ve already been putting the relics of space exploration there,” says Hamdan.

According to Hamdan, it’s hard to know whether the long-term effects of throwing satellites into the ocean has a positive or negative impact on marine wildlife and local ecology. But shipwrecks might offer some clues, she says.

When a ship runs aground, the microbes surrounding the wreck tend to be more diverse and play an important part in keeping the environment healthy. However, unlike vessels that sail across the sea, these structures orbiting Earth have traveled through space. The ISS, for instance, contains decades of experimental equipment, materials, and even traces of altered human DNA. It’s uncertain what kind of long-term effects the crafts—and what they carry—will have on Earth’s seabed.

“That’s going to be a really large human structure with a lot of human materials in it, that is now sitting on the seafloor,” She says. “It would be naive to think that that’s not going to change the ecology that’s present.”

[Related: This meteor-tracking system could prevent a falling-rocket debris disaster]

Space junk is just one type of marine debris that contributes to the increasing widespread pollution of Earth’s oceans. According to the Office of Coastal Management, more than 800 marine species have been injured, become ill, or died due to consumer plastics, metal, rubber, paper, and other debris. While the ISS is larger than most trash in the ocean, other experts are less worried about its immense size in comparison to other sunken junk.

“If you look at the volume of the International Space Station, it’s nothing compared to an ocean tanker,” says Cameron Ainsworth, an associate professor of physical oceanography at University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science. An average 700-foot-long tanker easily surpasses the ISS’s end-to-end length of 356 feet, making the station equivalent to “a few tons of aluminum crashing down into the ocean, which is going to be no more impactful than a ship sinking.”

But as Earth’s orbit becomes increasingly cluttered with more space junk crowding, those few hundred pounds of debris per craft will eventually add up.

“The ocean isn’t a limitless repository, for all of our space junk,” says Erik Cordes, a professor and vice chair of biology at Temple University. Cordes, who was one of many experts called in to help after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010, knows all too well the damage human activities can have on marine life.

Although he understands the appeal in landing decommissioned spacecraft as far from people as possible, Cordes says that there are a lot of “unpredictable” consequences to dropping tons of scientific equipment in an area that scientists historically don’t know enough about.

“People generally think of the deep sea as this big, muddy, barren desert, and that’s really not the case,” he says. “The more exploration we do, the more really amazing habitats and ecosystems and animals we start to discover on the ocean floor.”

[Related: The ocean is a giant dump for chemical weapons. Can we clean it up before it’s too late?]

Marine scientists often have to resort to making guesses about what’s lurking at the bottom of the ocean, Cordes says. But until they have real data, like high-resolution maps and images to scan the deepest parts of the seafloor, more work is needed before it becomes possible to predict what, if any, long-term impact dropping satellites into Earth’s oceans really has.

NASA states in the ISS decommissioning debrief that impacts to marine life are likely to be minimal: “During descent through the Earth’s atmosphere, the space station would burn, break up, and vaporize into fragments of various sizes. Some fragments of station [sic] would likely survive the thermal stresses of re-entry and fall to Earth. Environmental impacts of these debris pieces within the anticipated impact area would be expected to be small.”

When PopSci reached out to NASA and other government agencies for comment, they said that there are no official efforts to track space debris after it falls into the ocean. There is still time to explore other avenues or set up marine habitat monitoring before the ISS begins its decommission plans in 2030. NASA writes in the transition plan that it will continue “to investigate alternate footprint targets and ground paths for station disposal to minimize risk the to [sic] Earth’s population.” But until scientists know more, it’s a waiting game.

“I think with all the money that we spend to put this stuff up there,” Cordes says, “we should be spending a little bit of money finding out what happens when it comes back down.”