That time the CDC got people hyped for a zombie apocalypse

American medicine is rife with fringe science. A journalist shines a light on some of the most bizarre examples.

Excerpted from If It Sounds Like a Quack: A Journey to the Fringes of American Medicine by Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling. Copyright © 2023. Available from PublicAffairs, an imprint of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The year 2011, a tipping point for alternative healing, was important for another reason.

Deep beneath the Pacific Ocean, the edge of one tectonic plate was being jammed beneath the tectonic plate that held Japan. This wasn’t news. It had been happening at a rate of three inches a year since long before humans had invented the concept of news. But that March, it became news in the biggest possible way, when a chunk of the underlying plate suddenly gave way, causing the seafloor to pop up by about 15 feet and the plate holding parts of Japan to suddenly drop by about three feet. The magnitude 9 Tohoku earthquake was so big it shunted Japan eight feet to the east. It was so big it shifted the Earth six inches on its axis. It was so big it sped up the rotation of the planet

(only by 1.8 microseconds a day, but still—your days are now just a tiny bit shorter. Thanks Obama!). The earthquake and resultant tsunami also wreaked havoc on human systems—transportation systems, energy systems, water systems, telecommunication systems, and that most important of all human systems, the biological system that allows us to slobber, reproduce, and contemplate the irrationality of high baby-formula prices (usually in that order).

The tsunami killed more than twenty thousand people and caused multiple nuclear meltdowns, a disastrous toll for everyone except sellers of supplements, who pivoted to prey on the baseless fears of Americans living thousands of miles away from the radiation. Toby McAdam, still selling his RisingSun products, told the local newspaper that he doubted the radiation would drift to Montana—“but it could.” He recommended that his “Lugol’s Iodine solution” be applied to the skin daily as “an ounce of prevention.” Though public health officials said people self-treating with iodide supplements were more likely to harm than help themselves, orders spiked so sharply that Toby’s website crashed.

The multifaceted nature of the tsunami-caused chaos makes it perhaps appropriate that the event also marked the beginning of the United States’ descent into a full-blown zombie apocalypse.

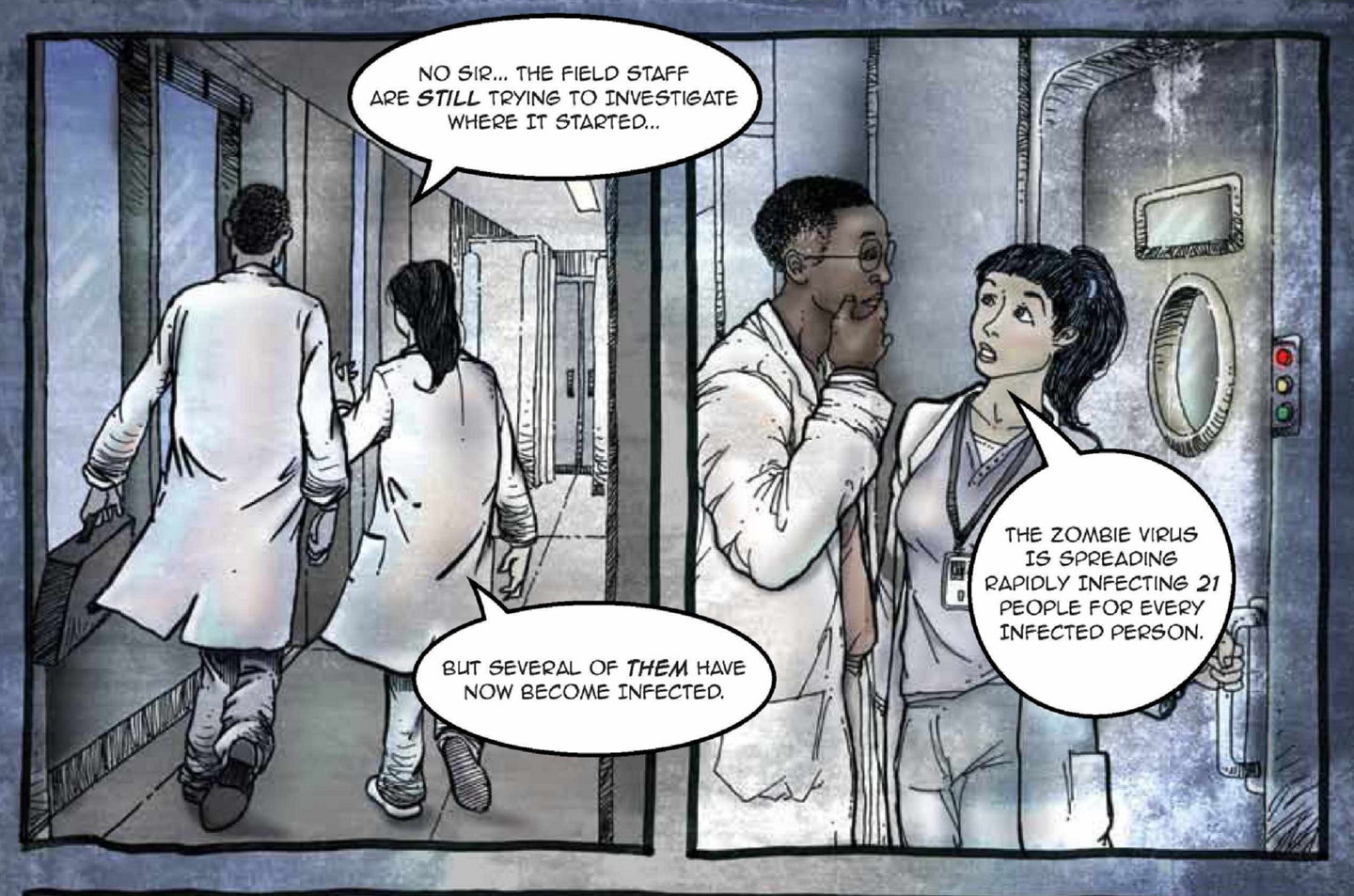

The June following the earthquake, the CDC began a conversation about emergency preparedness on Twitter that led to a handful of people jokingly tweeting that they would like the CDC to weigh in on a catastrophic zombie attack.

This led to the predictable wave of lols, rofls, and laughy-face emoticons, but it also sparked an idea for Dave Daigle (a CDC communications administrator) and Dr. Ali S. Khan (a CDC expert in disaster preparedness).

With Daigle’s input, Khan wrote a piece for the CDC website explaining how to prepare for a zombie apocalypse. This neatly demonstrated the humanity of the person on the other side of the icy-cold stethoscope even as it leveraged the innate appeal of zombies to teach real-life strategies to cope with actual disasters.

It turned out people were hungry for messaging about people hungry for brains. The CDC zombie apocalypse preparedness plan was an instant hit, racking up so many views that the CDC server froze up, overwhelmed by all the traffic.

This bit of fun was so successful that a team of researchers from the University of California, Irvine, published a congratulatory paper in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases urging other public health officials to follow suit. It argued that zombies were an opportunity “to capitalize on the benefits of spreading public health awareness through the use of relatable popular culture tools and scientific explanations for fictional phenomena.” They proposed that the medical establishment build o those efforts to stimulate the conversation and do better public education on a variety of health topics.

Suddenly, zombies were everywhere in public health and safety. The CDC, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency all published in-depth zombie-related literature. Finally, public officials were seizing the initiative and taking back the cul tural space they had inadvertently ceded to promoters of One True Cures.

Also in 2011, a Harvard Medical School physician and aspiring nov elist named Steven Schlozman appeared on the radio show Coast to Coast AM, which spun tales of conspiracy and paranormal phenomena to a large and credulous national audience from 2 a.m. to 4 a.m., seven days a week. Because Coast to Coast AM was the most popular late-night radio show in the country, with ten million listeners, it was a great opportunity for Schlozman, who was there to promote his latest work, The Zombie Autopsies: Secret Notebooks from the Apocalypse. In the book, Schlozman drew on his medical knowledge to describe “Ataxic Neurodegenerative Satiety Deficiency syndrome” as the medical cause

of zombies (it was of course a fictional work of fictitious fiction). The format of the show required that Schlozman spend the opening stretch talking about the events of his novel as if they were real, before shifting to an acknowledgment that it was all pure fantasy.

Daigle, Khan, and Schlozman were helping people learn a bit of science in a fun way.

But their efforts quickly ran up against a problem: there is more than one way to view a zombie apocalypse.

One fact that the CDC and its fellow agencies failed to fully appreciate was that, in zombie properties like 2009’s feature film Zombieland and 2010’s hit television series The Walking Dead, very little

screen time is given to public health concepts like water sanitation. The action takes place after most health authorities have had their faces eaten, leaving individual survivors to run around attacking infected people with baseball bats, crossbows, and shotguns as a means of self-preservation.

That’s why other groups were quickly lining up to enlist the hot new cultural craze into their own, very different agendas. Zombies became the centerpiece in gun advertisements and were a major part of the NRA’s annual conventions, where shooting at the undead carried none of the moral baggage that came with shooting at human targets.

“Because the zombie canon focuses so squarely on the apocalypse, its spread into popular culture can erode faith in the resiliency of civilization,” wrote Daniel Drezner, the Tufts University professor and zombie expert. “The zombie narrative, as it is traditionally presented, socially constructs the very narrative that agencies like the CDC and FEMA are trying to prevent.”

Drezner documented the way that zombie references became a sort of dog whistle for gun rights—those on the outside glossed over a quirky head-scratcher while targeted audiences became fired up, even though they would clearly never need to shoot a zombie in real life.

Until some Americans began to ask, Will I need to shoot a zombie in real life?

Toby McAdam had told me about the 2012 Miami incident in which a man bit the face off a homeless man and then was himself described by authorities as slow to die after being shot. But Toby was not the only person fascinated by that attack. It let the undead cat out of the bag.

Soon after the news broke, a self-described Bitcoin evangelist and promoter of alternative-health supplements doctored a Huffington Post article about the incident so that it attributed the cause of the face eating to “LQP-79,” a virus that destroys internal organs and makes the host hungry for human flesh.

The fake article went viral, blitzing digital media feeds so thoroughly that LQP-79 was soon the third-most-searched term on the CDC website, forcing the agency to officially deny the existence of a zombie virus.

Around then, communities of zombie-themed survivalists and militias sprang up all across America. One was an offshoot of the well-established Michigan Militia, while others had names like the Kansas Anti Zombie Militia, the Anti Zombie Unified Resistance Effort (AZURE), Zombie-Fighting Rednecks, the Zombie Eradication and Survival Team, Postmortem Assault Squadron, and the US Department of Zombie Defense.

One, a loosely affiliated national group called the US Zombie Outbreak Response Team (ZORT), popularized a strange mishmash of survivalism and cosplay. Its website features pictures of preppers in tactical gear and tinted sunglasses using stickers and goofy accessories to trick out their trucks as zombie-fighting vehicles that would be equally at home in Ghostbusters or Mad Max universes. It was in some ways good fun. But they also carried real firearms. And engaged in real postapocalyptic survival exercises.

“A Zombie could be anything from a person infected by a pandemic outbreak to a crazy nut job, criminal or gangster who wants to hurt your family and steal your food and preps,” reads ZORT’s promotional material.

Though ZORT purports to be simply providing tongue-in-cheek cover for legit training that would be helpful in a natural disaster, of course the real difference between zombies and hurricane survivors is that one must be shot in the head and the other should be given a hot toddy and a shower.

Did any of these folks actually believe in zombies?

Probably not. But there was potential.

Drezner cited research showing that when considering paranormal ideas, people look less to the logical evidence and more to whether other people believe in the ideas. This means that even if no one believes in zombies, if some people believe that other people believe in zombies, then some people will believe in zombies. The gaslighting became so effective that the gaslit then gaslighted others, until fear of actual zombies took on an undead life of its own—call it masslighting.

And really, the online picture was becoming quite blurry. At the CDC, Daigle and Khan began getting inquiries about their Zombie Preparedness Plan from concerned citizens who wanted to know what sort of firearm was recommended to repel undead invaders. Meanwhile, after his Coast to Coast AM appearance, Schlozman got emails from listeners who wanted to know what medicines could stave off a zombie infection, and whether he had recommendations for how to protect one’s home. China’s state media had to formally debunk a robust rumor that Ebola victims were rising from the dead as zombies. And in 2014 in the Florida statehouse, a representative formally proposed “An Act Relating to the Zombie Apocalypse” as the name of a bill that would allow citizens to carry firearms without a permit in an emergency.

Shockingly, a 2015 survey showed that 2 percent of American adults thought the most likely apocalyptic scenario would be one caused by zombies.

And zombie references kept popping up in unexpected places. People downloaded audio fitness tracks in which joggers were kept motivated by imaginary zombie antagonists that pursued them as they ran.

A man named Vermin Supreme, who sought the 2016 Libertarian Party nomination for president, added a platform plank on “zombie apocalypse awareness.” He also advocated using zombies for renewable energy. Even Big Tech was in on it. Buried in Amazon’s user agreement for a game-development engine, clause 57.10—a gag, probably?—read that the software should not be used in life-and-death situations, such as in medical equipment, nuclear facilities, spacecraft, or military combat operations. “However, this restriction will not apply in the event of the occurrence (certified by the United States Centers for Disease Control or successor body) of a widespread viral infection transmitted via bites or contact with bodily fluids that causes human corpses to reanimate and seek to consume living human flesh, blood, brain or nerve tissue and is likely to result in the fall of organized civilization.”

With zombie stories saturating popular culture, the lore in TV and film began to expand beyond the simple trope of shambling brain eaters. There were zombie rom-coms and zombie mockumentaries. On the CW Television Network, a show called iZombie tells the story of a Seattle morgue worker infected by a zombie virus. In this world, zombies retain their personality and capacity for reason, as long as they are well fed (on brains). During the third season, which aired in 2017, a militant group of zombies releases a deadly flu virus in Seattle; local public health officials announce a mandatory flu vaccination, only to find that the zombies have tainted the vaccines with a substance that will turn the vaccinated into zombies.

Vaccines that zombified ordinary citizens?

Luckily for public health, no one would believe that in real life.

Buy If It Sounds Like a Quack by Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling here.