Grisly medieval murders detailed in new interactive maps

A ‘perfect storm’ of hormones, alcohol, and deadly weapons made this English city a murder hot spot in the 14th century.

Fictional murderous barbers and real life serial killers are woven into London’s spooky history with legendary tales of their dastardly deeds. However, Sweeney Todd or Jack the Ripper may have paled in comparison to students from Oxford in the 14th century. A project mapping medieval England’s known murder cases found that Oxford’s student population was the most lethal of all social or professional groups, committing about 75 percent of all homicides.

[Related: How DNA evidence could help put the Long Island serial killer behind bars.]

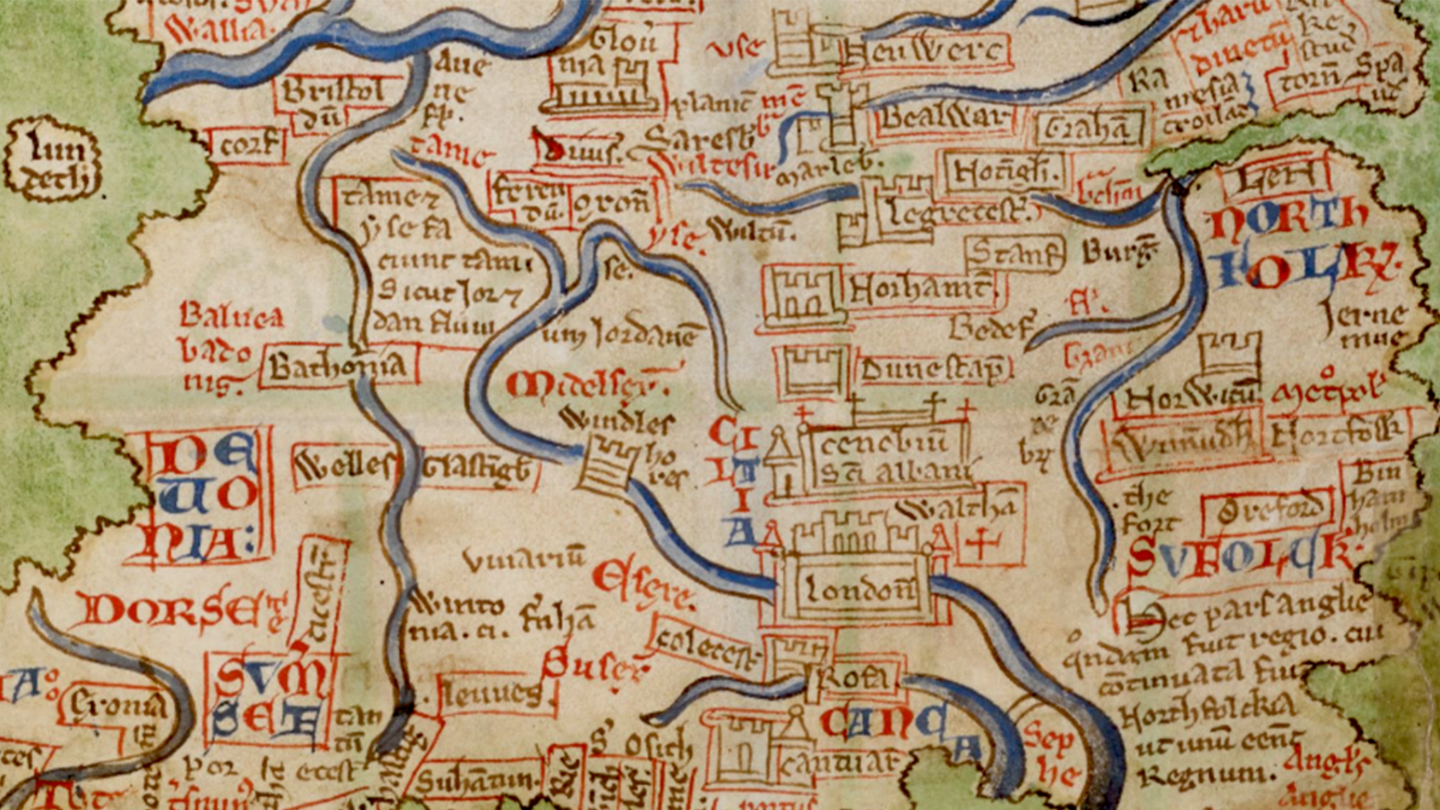

First launched in 2018, Cambridge’s Medieval Murder Maps plots crime scenes based on translated investigations from 700-year-old coroners’ reports. These documents were recorded in Latinand are catalogs of sudden or suspicious deaths that were deduced by a jury of local residents. They also included names, events, locations, and even the value of murder weapons. The project recently added the cities of York and Oxford to its street plan of slayings during the 14th century.

The team used these rolls and maps to construct the street atlas of 354 homicides across the three cities. It has also been updated to include accidents, sudden deaths, deaths in prison, and sanctuary church cases.

They estimate that the per capita homicide rate in Oxford was potentially 4 to 5 times higher than late medieval London or York. It also put the homicide rate at about 60 to 75 per 100,000—about 50 times higher than the murder rates in today’s English cities. The maps, however, don’t factor in the major advances in medicine, policing, and emergency response in the centuries since.

York’s murderous mayhem was likely driven by inter- knife fights among tannery workers (Tanners) to fatal violence between glove makers (Glovers) during the rare 14th century period of prosperity driven by trade and textile manufacturing as the Black Death subsided. But Oxford’s rambunctious youth made for a dangerous scene.

By the early 14th century, Oxford had a population of roughly 7,000 inhabitants, with about 1,500 students. Among perpetrators from Oxford, coroners referred to 75 percent of them as “clericus.” The term most likely refers to a student or a member of the early university. Additionally, 72 percent of all Oxford’s homicide victims also have the designation clericus in the coroner inquests.

“A medieval university city such as Oxford had a deadly mix of conditions,” lead murder map investigator and University of Cambridge criminologist Manuel Eisner said in a statement. “Oxford students were all male and typically aged between fourteen and twenty-one, the peak for violence and risk-taking. These were young men freed from tight controls of family, parish or guild, and thrust into an environment full of weapons, with ample access to alehouses and sex workers.”

Many of the students also belonged to regional fraternities known as “nations,” which could have added more tension within the student body.

One Thursday night in 1298, an argument among students in an Oxford High Street tavern resulted in a mass street fight complete with battle-axes and swords. According to the coroner’s report, a student named John Burel had, “a mortal wound on the crown of his head, six inches long and in depth reaching to the brain.”

Interactions with sex workers also could end tragically. One unknown scholar got away with murdering Margery de Hereford in the parish of St. Aldate in 1299. He fled the scene after stabbing her to death instead of paying what he owed.

[Related: A lost ‘bawdy bard’ act reveals roots of naughty British comedy.]

Many of the cases in all three cities also involved intervention of bystanders, who were obligated to announce if a crime was being committed, or raise a “hue and cry.” Some of the bystanders summoned by hue ended up as victims or perpetrators.

“Before modern policing, victims or witnesses had a legal responsibility to alert the community to a crime by shouting and making noise. This was known as raising a hue and cry,” co-researchers and Cambridge crime historian Stephanie Brown said in a statement. “It was mostly women who raised hue and cry, usually reporting conflicts between men in order to keep the peace.”

Medieval street justice was also coupled with plentiful weapons in everyday life, which could make even minor infractions lethal. London’s cases include altercations that started over littering and urination that led to homicide.

“Knives were omnipresent in medieval society,” said Brown. “A thwytel was a small knife, often valued at one penny, and used as cutlery or for everyday tasks. Axes were commonplace in homes for cutting wood, and many men carried a staff.”

The team told The Guardian that they hope this project encourages people to reflect on the possible notices behind historic homicide and explore the parallels between these incidents and the altercations in the present.