How to spend your money for maximum happiness

Years of behavioral and psychological research have given us insight into how to splurge optimally.

The idea that materialistic values can obstruct our path to happiness dates back hundreds of years. The Buddha encouraged a balance between asceticism and pleasure; early Christian monasticism preached spiritual transformation through simple living; philosopher Lao Tzu warned that if you chase after money, “your heart will never unclench.”

Centuries later, the question of whether money can bring us happiness remains a subject of intense debate. After all, as our culture of consumption expands exponentially, our lives increasingly revolve around money—Earning it, spending it, and saving it.

Consider the numbers. Between 1901 and 2003, U.S. household spending increased 53-fold, from $769 to $40,748 (that’s $2,000 in 1901 dollars). And what we spend on has also changed. Today, the average American family spends about 50 percent of their income on necessities like food and shelter, compared to almost 80 percent in 1901. That means more discretionary spending on consumer goods and services, including the 11.3 million tons of clothing and 27 millions tons of plastics that end up in U.S. landfills every year.

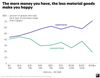

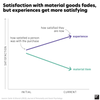

But though the things we buy might make us happy in the moment, that feeling atrophies over time. It’s what psychologists call the “hedonic treadmill,” says Amit Kumar, an assistant professor of marketing and psychology at the University of Texas at Austin, whose research focuses on the science of happiness. “We get used to things that we have, and when new, shiny things are advertised, we feel like we need to keep getting more stuff to maintain those feelings.”

So does money bring us happiness, or is it the root of our misery? It’s complicated. Financial security certainly influences our well-being when it comes to satisfying our basic needs and standard of living, but in general, research shows affluence is a weak predictor of happiness.

What most experts can agree on is this: there are ways to spend our money that are more likely to elicit joy. So next time a commercial has you itching to pull out your wallet, hit pause and consider these three tips on where to invest your cash.

Time is precious—buy yourself some more of it

We can send messages anywhere in the world instantly, travel across oceans in a matter of hours, and get almost anything we can dream of hand-delivered to our doorsteps within days. And yet despite our ability to do nearly everything faster and more efficiently, people across all income levels report experiencing a phenomenon known as time famine.

“It isn’t necessarily how busy your calendar is, but rather the internal state of anxiety and concern that you don’t have enough time to do the things you want to do,” Kumar explains.

Time famine isn’t just an existential crisis—it can have real consequences on our health. Research shows that people who feel time-constrained are more stressed, less likely to spend time helping others, and less active. It’s also one of the main reasons people give to explain why they’re not exercising regularly or eating well.

But receiving social support may protect us from the negative consequences of time stress, a concept psychologists call the buffering hypothesis. According to this theory, buying time—by doing things like hiring a house cleaning service instead of tidying up, ordering takeout instead of cooking, or paying extra for a direct flight—can increase our sense of control and, ultimately, our feelings of well-being.

The caveat? The amount of disposable income we have makes a difference when it comes to buying time. If paying someone to clean your house means cutting your grocery budget for the week in half, those hours of reclaimed free time won’t pack the same punch as they might if they were funded by spare change.

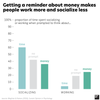

We’re also less likely to benefit from buying time when we focus on its economic value—something we’re more likely to do if we have less cash to go around. For example, research shows that hourly-wage workers tend to apply “mental accounting rules” to their time, which can affect how they budget it and how much they enjoy it. In a series of 2012 experiments, psychologists found that when participants were primed to think of their time as carrying monetary value, they were more impatient and experienced less pleasure during leisure activities like listening to music.

Another review of 165 studies from 18 countries yielded two major findings. First, that focusing on finances isn’t all bad. Money-focused individuals are indeed productive—reminding people about money motivates them to exert extra effort on challenging tasks, to put in longer hours, and to perform better. On the flip side, they also tend to work more, socialize less, and experience greater psychological and physiological stress.

In their book, Happy Money: The Science of Happier Spending, authors Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton sum up this paradox: “By permitting us to outsource our most dreaded tasks, from scrubbing toilets to cleaning gutters, money can transform the way we spend our time, freeing us to pursue our passions,” they write. “Yet wealthier individuals do not spend their time in happier ways on a daily basis; thus they fail to use their money to buy themselves happier time.”

The key takeaways? First, treat time as the commodity. Research suggests that people who think of their time as a limited resource in its own right are more likely to derive joy from life’s simple pleasures, like eating sweets or talking to a friend.

Second, if you’re splurging on a time-saving purchase, use those extra minutes to do something that lifts your mood. Studies on time and happiness show people typically experience more positive emotions during leisure activities compared to when they’re working or doing household chores. Active and social forms of leisure, like exercising and volunteering, are also linked to greater happiness compared to more passive activities, like watching TV or napping.

“The more that people are using their time to engage in social interactions to cultivate relationships, the more happiness they’re going to get from buying time,” Kumar explains. That’s why buying experiences is another way to maximize joy from spending.

Invest in experiences

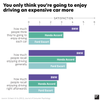

You might think it’s more practical to spend money on something that you’ll use for years rather than on a fancy dinner or vacation. But research suggests that an intangible experience can often bring you joy for longer than a physical object.

“People believe material goods last—and they do last in a physical sense, but that doesn’t mean you continue to derive value from it,” Kumar says. “Experiences are fleeting, but not in a psychological sense. They live on in our memories, they live on in the stories we tell.”

For example, people get boosts of pleasure from planning and anticipating experiences, like vacations—and then again when recalling those memories later. That’s partly because experiences often cultivate connection and feelings of belonging, whereas we’re more likely to consume material purchases alone.

We’re social animals, after all. In Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, as soon as our basic needs—food, shelter, and safety—are met, the first thing we seek is companionship. Research on human flourishing confirms that cultivating meaningful relationships through institutions like work, religious communities, and marriage enhances our well-being, and is associated with better health and longer life expectancy.

Our experiences also play a significant role in the formation of our identities. “Experiential purchases tend to be more reflective of a person’s identity and their sense of self,” Kumar says. “Our stuff is less centrally tied to who we are. We’re the sum of our experiences.”

That’s why people bond with each other over experiences rather than their possessions. “It can be annoying to find out that someone has a nicer TV or a fancier wardrobe,” Kumar says. “These comparisons can make people feel worse.” It turns out experiences are less susceptible to these types of problematic comparisons. “People don’t want to trade their trip for someone else’s. Your experiences are kind of uniquely yours.”

Even spending time on simple, low-cost pleasures, like attending an exercise class or drinking a cold beer with friends, can produce small, frequent boosts in mood and facilitate social connections. And since the COVID-19 pandemic has forced most of us into physical isolation, we need to get more creative than ever. That could mean signing up for a virtual painting class, “sharing” a fancy bottle of wine during a Zoom happy hour, or investing in outdoor recreation. “Get out and hike and bike and take advantage of your local environment,” says Thomas Gilovich, a professor of psychology at Cornell University who studies human judgment. “These kinds of experiences don’t demand a giant bank account.”

You don’t need to make extreme lifestyle changes either. “It’s not that the material goods are bad and you have to stop purchasing them,” Gilovich explains. “It’s just if you shift your expenditures a bit more in the experiential direction and a bit less material direction, you’ll be happier.”

Spend on others

Another benefit of investing in experiences is that they inspire us to engage in more altruistic behaviors. “We found that when people think about experiences rather than possessions, they end up being more generous to others,” Kumar says.

That’s because we tend to be more thankful for what we’ve done than we are for what we have. Those feelings of gratitude comes with a whole host of psychological benefits, including prosocial behaviors like giving.

This is significant because spending money on others is also linked to greater well-being. One survey of 136 countries found that prosocial spending was universally associated with greater happiness in both wealthy and poor countries. In lab experiments, participants who were randomly assigned to spend money on others reported greater happiness than those assigned to spend it on themselves.

In fact, we may be hardwired to give. Children start to demonstrate prosocial behaviors like sharing as early as age two, and they’re linked to our brains’ reward systems. Evolutionary theorists argue that altruistic behavior is a survival trait, much like eating or having sex. It was crucial for the large-scale cooperation that allowed early humans to survive and thrive in groups.

Today it serves another adaptive function: it’s good for our health. For instance, studies show that helping others is linked to a decreased risk of morbidity and mortality in older adults, that people who give social support are more likely to receive it in return, and that giving social support is related to positive health outcomes like lower blood pressure.

It also affects our brains. An fMRI experiment examining the neural bases of altruism found that when people gave to charities, brain areas associated with pleasure and social attachment were activated—something known as the “warm glow” effect. The best part: generosity is contagious and can influence the spending habits of those around us. For example, in a series of experimental “games,” researchers found that when one person gave money to help another, the recipient was more likely to give their own money away during subsequent games.

But sometimes the details matter. When it comes to giving, spending money on people we have stronger emotional ties with may be more likely to boost happiness compared to weak or anonymous relationships. Likewise, when it comes to charity, giving to a specific cause or mission can produce greater feelings of happiness compared to a more general donation. Psychologists suggest that’s because you know exactly how your money is going to benefit the recipient.

Focus on human connection

So is shifting our spending habits away from material things the key to bliss? Despite a sea of research, there’s still no tidy answer. Happiness is notoriously difficult to study; it’s subjective, unstable, and intangible. But one common thread consistently comes up in the research: the power of human connection to elicit joy.

“Purchases that help to foster our social relationships—those are the purchases that are most likely to bring us longer-lasting, more enduring happiness,” Kumar says.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean spending all your money on family vacations: sometimes material purchases are vehicles for social connection. The idea is to invest more in experiences than in possessions, Gilovich explains, but sometimes the latter can facilitate the former. “There are things sort of in the middle,” he says. “You buy a new bike, you get together with a bunch of cyclists, and you cycle regularly.” His advice: when you’re buying something, ask yourself how likely you are to use it with other people.

Kumar agrees. “One of the mistakes that people can make is that they think that material goods are a better financial investment, that they’ll last,” he says. But the material goods that pack the biggest punch are the ones that beget social experiences.

For him, the recipe for better spending is simple: “Positive social relationships are essential to human happiness—spend money in ways that advance your social relationships [and try to] minimize making comparisons to other people.”